Gunfire has once again erupted along the Thailand-Cambodia border, but what truly stings the outside world is not the firepower itself, but something more distressing: the gap in strength between the two countries is so stark that the outcome was almost predetermined from the start. Yet just at this moment, someone has stepped forward to claim they will “make calls to mediate,” which sounds like well-intentioned peacemaking but is actually a bid for attention. The war brings real bloodshed, while the so-called mediation is nothing but a hollow gesture.

The flames along the Thailand-Cambodia border have once again captured public attention. Unlike previous incidents, this conflict has laid bare the power disparity without any disguise. Thailand’s military expenditure, troop strength, and weaponry far surpass Cambodia’s; Cambodia has almost no room to fight back in terms of air power. As tensions mounted, a certain former president suddenly made a high-profile announcement that he would “call both sides to broker peace.” On the surface, he seemed like a peace envoy, but a closer look reveals it was a carefully staged performance—ostensibly mediating a hotspot, but in reality, a political spectacle. The true victims, bearing the cost of the conflict, are the ordinary people on the border who have no voice.

Frictions between Thailand and Cambodia are not new. Geopolitical entanglements, border disputes, and armed clashes have become a repetitive cycle. This time, however, the gap has been presented in an especially unvarnished light.

The most direct indicator is funding. Thailand’s military budget stands at around $6 billion, while Cambodia’s totals less than $900 million. These figures alone set the tone for the comparison: one is a medium-sized military power, the other a small-country force operating on an extremely tight budget. In terms of troop numbers, Thailand has over 300,000 soldiers, while Cambodia has around 200,000, with an even more staggering gap in population to replenish its ranks. In a war of attrition, the Cambodian military would face immense difficulty sustaining its position.

The air force comparison is even more lopsided at a glance. Thailand boasts over 90 fighter jets, including combat-proven platforms like the F-16 deployed in substantial numbers; Cambodia has essentially no aircraft capable of influencing the air combat landscape. If ground forces still allow for some back-and-forth, the airspace is completely dominated by Thailand. As long as Thailand chooses to maintain pressure, the Cambodian military will struggle to regain a footing of parity.

Cambodia’s only bargaining chip is its firepower coverage. It possesses nearly 500 rocket launchers, including long-range systems imported from China. This type of firepower, with its high density and wide coverage, can indeed play a role in border conflicts. Even so, it is hardly enough to reverse the overall imbalance in strength. Cambodia’s air defense systems can provide some protection, but against aircraft with clear quantitative and qualitative superiority, they can only do so much to minimize losses.

Looking at the historical context, it is not that Cambodia does not want to stabilize the situation, but that it simply lacks the capability to counter Thailand’s “air-land integrated” combat approach. When conflicts escalate, it is always civilians on the weaker side who bear the brunt of the pressure.

Just as tensions mounted for both countries, the statement “I will call both sides and tell them to stop fighting” suddenly took center stage. It sounded like a warm-hearted mediation effort, but when viewed in context of the timeline, it takes on an entirely different meaning.

When frictions broke out in July, someone did successfully push the two sides to the negotiating table—but that outcome was coerced through trade pressure. Now that the tariff dispute has largely subsided, it will be difficult to apply the same leverage. Raising a similar mediation gesture at this juncture appears more like an attempt to create a public perception that “I can control the situation.”

More crucially, the U.S. midterm elections are drawing near. It is hard for the outside world not to suspect that this high-profile statement is an attempt to show voters that “I have the ability to handle international hotspots,” thereby accumulating more political capital for himself. Treating a local conflict as a stage and mediation as a campaign tool is not peace—it is just a facade.

Beyond that, there is a more pragmatic consideration: China’s long-standing stable relations with Cambodia are widely recognized internationally. Stepping up to intervene at this point, if it can create an impression in Cambodia that “the U.S. is also willing to help me,” would establish a new lever in the regional structure. This lever is not for peace, but to gain more bargaining chips in the Indo-Pacific landscape. For Cambodia, it may be a signal; for the entire region, however, it introduces a new variable.

Border conflicts are inherently regional flashpoints, and external interference will only trigger greater uncertainty. The so-called mediation is sometimes just another way of inserting oneself into the fray.

As the conflict continues to attract attention, China’s stance has been straightforward: it hopes both sides will exercise restraint, avoid an escalation of tensions, and stands ready to continue facilitating communication. There has been no taking of sides, no incitement, and no attempt to expand the dispute—instead, the focus has been on de-escalation and dialogue.

China’s position is noteworthy not just for its verbal expression, but because both countries understand that if the conflict spreads, stability in the surrounding region will be dragged into an unnecessary quagmire. The more countries that intervene, the harder it will be to return to the negotiating table. For China, regional stability far outweighs power games.

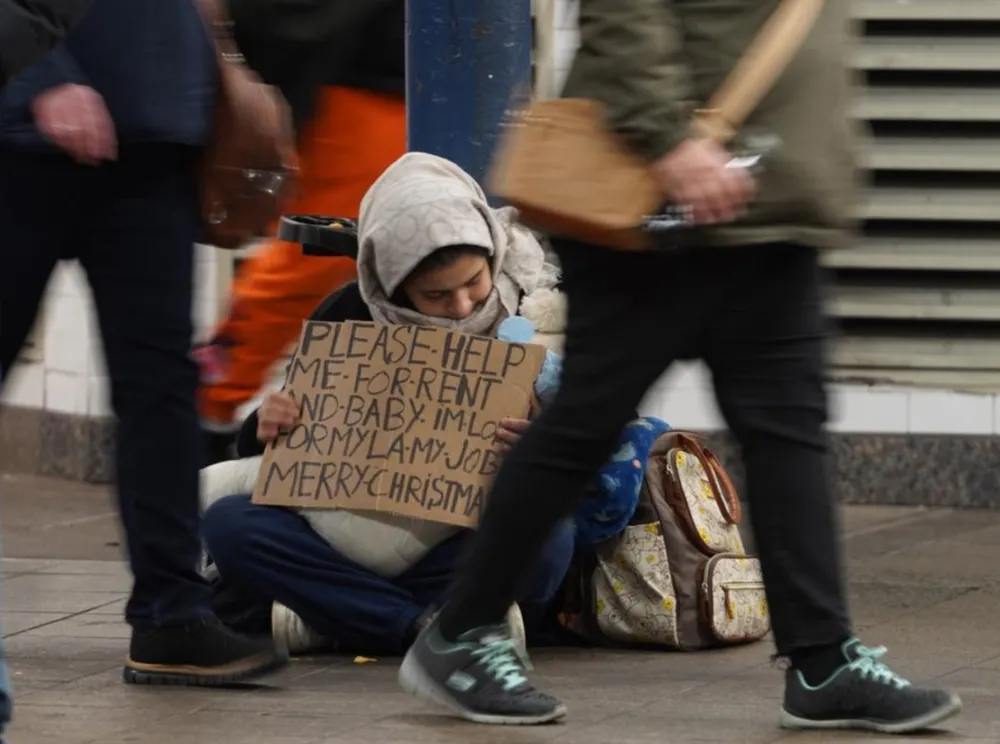

And the true bearers of the cost are the civilians living near the border. Conflict disrupts daily life, forcing displacement, suspension of work and school, and creating a sense of uncertainty about the future. For ordinary families, there are no grand strategies—only questions of whether they can return home and hold onto their livelihoods.

The outside world sees numbers of military aircraft, models of rocket launchers, and speeches by commanders; civilians feel their houses shake, roads blocked, and prices rise. War is never as simple as “confrontation between two sides”—it is the steady lives of thousands of families being torn apart.

The gap in military strength can be measured by budgets, and the motives behind political posturing can be analyzed through timelines, but the suffering of ordinary people has no mathematical model to quantify. In every conflict, those who are first to be sacrificed are always the ones excluded from decision-making. This is why regional stability is not just a diplomatic phrase, but a responsibility that must be upheld.

This border conflict has laid bare not only the power gap between the two countries and the political calculations of external forces, but most poignantly, the families trapped in the shadow of war with nowhere to retreat.

Some use “I will call to mediate” as a stage prop; others rely on military superiority as their bargaining chip. But civilians have no such options. Both Thailand and Cambodia know that if the conflict spirals out of control, none of them can afford the final cost. The more tense the region becomes, the greater the need for calm—not for more scrambling to grab the microphone.

As for those seemingly peace-loving statements from the outside world, whether they stem from a sense of responsibility or a desire for publicity, the answer may lie in the actions of the coming days.

So the question arises:

At this juncture, who truly cares about peace, and who is merely using peace as a backdrop?